REVUE DE PRESSE

Note d'intention de Catherine Breillat concernant Une Vieille Maîtresse

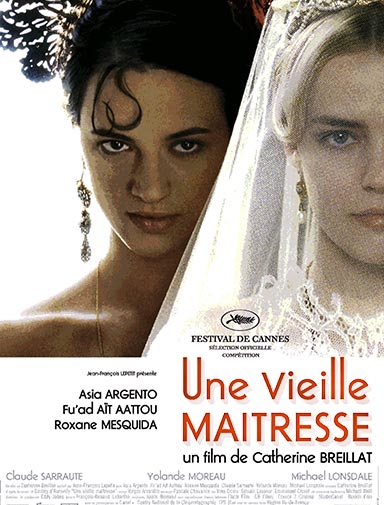

« Une Vieille Maîtresse », c'est la parabole d'une liaison qui semble passée, et dont on mésestime la force car on la croit usée par la durée ; -lorsqu'elle n'est qu'un volcan très momentanément endormi.

The last mistress

In Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress, bleeding is love, both carnal and pure, cutting skin and stigma. It transcends any societal scruples, any better judgement, leaving bare the maidenly point where love and lust quit their fight and unite.

CATHERINE BREILLAT : "LE JOLI EST AFFREUX"

La cinéaste sera demain vendredi et samedi au Festival Zoom Arrière de Toulouse où elle viendra discuter censure et interdits et présenter trois de ses films.

CATHERINE BREILLAT RETROSPECTIVE : ALMOST MAINSTREAM

Catherine Breillat has and hopefully will continue to be an essential voice in cinema, telling tales about women and from a woman’s perspective that are too often lacking. Watching her develop into a truly accomplished technical filmmaker and storyteller is really exciting and makes one anxious for what will follow.

Sex and Power: The Provocative Explorations of Catherine Breillat

The work of Catherine Breillat, the French filmmaker and novelist whose movies frequently explore the perversity animating male-female power dynamics in Western society, has always been fearlessly pertinent. These days, as more and more revelations about the sexual predations of high-profile men come to light, they may even be more pertinent.

Note d'intention de Catherine Breillat concernant Une Vieille Maîtresse

Le roman m'a immédiatement fasciné car au-delà du ton romanesque et romantique, on y sentait une vérité de sentiment crue, une analyse de la passion avec ce qu'elle comporte d'irrationalité et de délectation dans ses vertiges, qui font que loin d'y échapper, on souhaite y sombrer.Barbey d'Aurévilly ne s'en cachait pas, le fondement du livre était autobiographique et le personnage de Vellini inspiré d'une liaison fatale et singulière. De celle qu'on n’avoue pas et qui s'étale ici avec une sincère impudeur qui lui valut l'opprobre et les scandales de l'époque.Cette sincère impudeur dont je fais profession moi aussi, et qui me semble à travers le siècle qui nous sépare comme en gémellité, en écho avec celle de Barbey d'Aurévilly.

Moi qui n'ai jamais eu jusqu’ici de goût particulier pour les adaptations romanesques, je me plais à penser que si j’avais vécu à son époque, j’aurais été semblable à Barbey d’Aurévilly. Je me reconnais dans son roman. Il s’est emparé lentement de moi comme un second moi-même qui m’apporterait providentiellement la dimension romanesque que je n’ai pas, et qui est tellement nécessaire à ce que je veux : faire du cinéma populaire et néanmoins sophistiqué.

« Une Vieille Maîtresse », c'est du « roman populaire à personnages compliqués », où les grands premiers rôles sont d'une pureté paroxystique, quasi chimérique dans le noir ou le blanc.

La déconsidération dans laquelle se vautre Vellini et Ryno avec elle, ne participe-t-elle pas du même orgueil d'âme que l'impassibilité dans la douleur à laquelle se contraint Hermangarde : cette imagerie contrastée nous met à deux pas du roman, (et donc du film) populaire.

Hermangarde, est une sorte d'Iseult au visage aussi immaculé que sa chevelure. Pure et transparente comme un diamant bleu. De la limpidité absolue des paupières, de l'arcade sourcilière au bord soyeux des cils, du gonflement purpurin des lèvres, elle a cette particularité de la fin de l'enfance qu'on remarque dans les tableaux Renaissance indifféremment chez toutes jeunes femmes ou hommes de quatorze, quinze ans.

Ryno de Marigny est un jeune homme trop beau et pour cela faible. Faible comme une fille. Lâche et sublime dans la passion.

Même si on lui prête un pouvoir diabolique : parce que toutes les femmes sont prêtes à se damner pour lui. Ou plutôt pour son image, - cette beauté, cette grâce dont si même elle ne la possède pas, Vellini en possède le pouvoir, -alors que Ryno qui l'a, n'en porte que le fardeau.

Quant à la Marquise de Flers, n'est-elle pas la seule que Ryno puisse se laisser aller à sincèrement aimer, quand la barrière de l'âge interdit toute émotion triviale et vulgaire des sens; -et qu'elle-même peut pour la même raison se croire à l'abri des dangereuses séditions de l'amour et du désir.

Car comme toujours, c'est de culpabilité qu'il s'agit ici, lorsque dans la tempête des passions chacun croit de son honneur de rester le capitaine de son navire. Et c'est bien cela, -à cause de cet orgueil insensé, ce refus de reconnaître l'amour par son nom, de ne l'appeler que désir, d'en craindre l'asservissement et le joug, -qui précipite le naufrageur.

Comme le Valmont des Liaisons Dangereuses que cite, qu'admire et redoute la Marquise de Flers.

Tandis que la Vellini, seul personnage exemplaire dans la passion, sait très bien de quoi il retourne; et que l'amour est un enfer de boue qui, -si on ne craint pas de s'y salir les mains, voire de s'y vautrer tout entière, -apaise les brûlures en même temps qu'il en attise le feu.

Le filtre de l'époque, le transfuge de l'auteur romantique pour qui il n'existe pas de juste milieu entre la sylphide et la catin, pour qui les femmes ne peuvent être que des saintes ou des damnées (et en définitive l'objet de la même exaltation), sont pour moi un nouvel et capital enjeu.

Ce n'est pourtant pas une reconstitution d'époque à laquelle je veux me livrer, -ce qui me fascine est bien la modernité, l'implacable vivisection du sentiment passionnel.

L'époque est le nécessaire écrin de cette modernité parce que les sentiments ne fonctionnent comme éternels dans notre imaginaire présent que lorsqu'on les y laisse... qu'on les y laisse errer en toute liberté dirais-je.

Car dans le roman, (et il en sera de même dans le film), -il n'y a pas de place à d'autres préoccupations que ces liaisons si dangereuses que la Marquise de Flers invoque souvent, se retranchant derrière Choderlos de Laclos en le nommant comme de son siècle, (c'est-à-dire toujours présent) au mépris de la vérité historique qui veut qu'un siècle (fusse un demi) les sépare.

Le tout dans le Paris de ce Faubourg Saint-Germain où est éclos l’esprit Français propre à cet analyse des sentiments qui de Marivaux mène à Rhomer et même Sagan… Paris des hôtels particuliers d’une sobre élégance aux boiseries dorées, l’art Français dans sa magnificence, mais aussi, ce Paris qui ressemblait si vite à un village, avec ses petites bâtisses de pierre, ses murs, ses espaces ici et là abandonnés à une végétation folle, ses métiers disparus, rémouleurs, distributeur d’eau…

Je pense que les lieux doivent être là pour créer de la poésie, comme les silences d'une partition musicale particulièrement fiévreuse où croches et triple croches se superposent dans un train infernal au rythme des assauts d'un dialogue aux ambages littéraires, denses et acérés.

J'aime ces joutes de paroles interminables, où les vérités s'affrontent pour en dissimuler toujours une autre, plus intime, celle qu'on se cache toujours à soi-même, -et que le cinéma, ce microscope implacable exalte si bien...

Inutile donc de dire que le microscope, c'est le gros plan, l'inquisition au cœur de l'intime des personnages, la quête des abandons et des fièvres, des reniements et des exaltations: Car lorsque les âmes et les visages sont nues, qu'importe l'époque : nous sommes tous les mêmes: la proie de nos chimères.

Pour « Une Vieille Maîtresse », je désire exalter dans le film ce sens si anodin du titre où l'article indéfini accorde de l'importance à ce qui n'en a généralement pas, non point l'âge de l'héroïne, mais la durée, la pérennité du sentiment : « Ce goût enragé et passé à l'état chronique, sans cesser pour cela d'être à l'état aigu » ; et qui est peut-être, (selon Barbey lui-même), la meilleure définition qu'on puisse donner de l'amour.

« Une Vieille Maîtresse », c'est la parabole d'une liaison qui semble passée, et dont on mésestime la force car on la croit usée par la durée ; -lorsqu'elle n'est qu'un volcan très momentanément endormi.

Retrouver la modernité du roman, c’est aussi épurer, comprendre les métaphores, les paraphrases rendues nécessaires par la censure drastique de l’époque.

Ainsi je pense dans un travail de réécriture/ré-interprétation effacer presque complètement du scénario le mythe (vieillot et un peu conventionnel) du « pacte du sang ». Si celui-ci doit exister comme un jeu amoureux, ce n’est pas lui qui scelle les destins de Ryno et de la Vellini.

Il me semble qu’il faut plutôt privilégier d’y voir, (comme une brève clarté de l’époque, bientôt balayée par l’advenue de la révolution et la montée en puissance d’une bourgeoisie impitoyablement collet monté, -ici les femmes sont encore décolletées à outrance, - c’est la mode romantique comme dans « Le Guépard »), - il faut donc plutôt y voir l’affrontement entre la beauté convenue d’une vierge icône, femme et jeune fille de toujours dans une dissimulation idéale de ses sentiments et le refoulement des désirs, qui représente la « fiancée idéale », -et la « femme souveraine », l’amazone qui prend ce qu’elle désire et dont les désirs affirmés sont la beauté, cette beauté si récriée dans le monde où on réprouve sous le nom de « laideur » la liberté affichée d’une femme, sa sensualité manifeste et le pouvoir que cela lui donne sur les hommes.

Séductrice contre séducteur, -même le plus redoutable d’entre eux, - c’est elle encore qui gagne.

Femme perdue, sans position sociale, sans avenir et même sans véritable beauté, c’est elle qui gagne car elle est l’imagerie même de la femme fatale, ce mythe cinématographique qui cache un des enjeux de notre époque : Sexualité contre convenance, ce duel-là me fascine et je veux en filmer la chair.

The last mistress

In Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress, bleeding is love, both carnal and pure, cutting skin and stigma. It transcends any societal scruples, any better judgement, leaving bare the maidenly point where love and lust quit their fight and unite. The lovers in this story, adapted from the novel by Jules Amedee Barbey d'Aurevilly, are only virginal in one respect, to be revealed and remembered in the perfection of blood red.Breillat has previously explored myriad forms of sexual violence: deviant, celebrated, and sometimes the combination of the two. The Last Mistress is a new chapter in this inspection, taking cues from her previous films Romance and Fat Girl. She also revisits expectations, utilizing a magician-like ability to create illusions despite the viewer’s “I’m not gonna get screwed by Breillat this time!” persistence. But pulling the carpet from under your feet goes beyond mere gimmickry in The Last Mistress. The film weaves a familiar story of infidelity on the surface, yet preys on our own passing judgements on the quality of love of friends and strangers, when we convince ourselves ignorance is intuition.

The story begins and ends, without spoiling anything, with two elder nineteenth century aristocratic French gossipers, pondering a relationship of young lovers with the frenzied lack of consciousness of an Us Weekly magazine. In fairness, the assessment is plausible with only mildly interested eyes. Ryno, a Parisian playboy on the cusp of a marriage to a society sweetheart, does a bad job having a quiet affair with a tempestuous Spanish woman ten years his senior. He seemingly uses her and perhaps all women but pledges to “make the straight play” for his new girl wonder, similar to R&B ballads of usually self-proclaimed players. Yet in flashbacks, not surprisingly, a more nuanced truth is revealed. Ryno, (well played by Fu’ad Ait Aattou, overcoming his runway looks) had started as a fed up French gigolo. When sleeping with well-to-do married women bores him, he is temporarily lost before encountering Vellini, the untamed fire of a woman who is branded into his subconscious, a creature of animalistic proportion and honesty that, once discovered, he would fail to dispossess.

Vellini is played to perfection by the actress Asia Argento, daughter of Italian horror master, Dario Argento, and perhaps Catherine Breillat’s new muse. There appears to be an ideal synchronicity to the actress and director, as if they may have been finishing each other’s thoughts on opposite sides of the lens. Argento’s impassioned rawness has been in the works for years now, from horror in the tradition of her father, like Land of The Dead, to the misbegotten, The Heart is Deceitful Beyond All Things. But never has a director honed that primitive energy into a performance of fine distinction until Breillat honed it in The Last Mistress. As Ryno falls in love with such an unlikely heroine/femme fatale, so do the camera, and eventually the viewer. The relationship ebbs and flows behind the weight of its colossal craze, so primordial as to trump convention, and possibly its ability to exist.

Breillat continues to avoid being lumped into the current French “mini-new wave,” with its Polanski obsessions so embodied in the overrated films of Francois Ozon. She maintains her own place among the top filmmakers of today, not emboldened by scene or association. At the heart of her talent is her simple ability to tell a story with such deftness that it can result in a sort of surrendered hypnosis, leaving a viewer wilfully vulnerable and manipulated, guided only by the trust that something can actually be learned through this capitulation, a rarity in modern cinema.

The Last Mistress ends with the futures of the lovers indeterminate. The bond always soaring or burning, but never steady. Yet the mystery is why, through all the tumult, the characters are to be envied.

Kevin Cooke

CATHERINE BREILLAT : "LE JOLI EST AFFREUX"

Chacun de ses films est sujet à controverses. Autant dire que la réalisatrice Catherine Breillat s'imposait comme invitée du festival « Zoom arrière » consacré aux films interdits. Explications de la réalisatrice…Entre la censure et vous, c'est une histoire ancienne…

J'ai écrit « L'homme facile » mon premier roman, à 16 ans. Il a été interdit aux moins de 18 ans, ce qui veut dire que suivant la logique de la censure, je ne pouvais pas relire ce que j'avais moi-même écrit. J'étais alors une jeune fille brillante, différente, qui se posait des questions sur tout… Bref, la censure, qui est le reflet de la société, n'aimant pas la singularité, j'ai été interdite…

Craignez-vous la censure ?

Non, pas du tout. La censure, j'ai toujours dialogué avec elle. Et aucun de mes films n'a jamais, d'ailleurs été interdit. Et pourtant, je vais toujours plus loin.

Vous dialoguez avec elle ?

Oui, dialoguer avec elle, c'est lui demander « pourquoi ? » ; le problème n'étant pas ce qu'on voit, mais à quoi ça sert. Je prends l'exemple de « Romance» (N.D.L.R. avec Rocco Siffredi), le film ne peut pas être classé X car mon but n'est pas de faire un film masturbatoire. Au contraire, je trouve que le film est très froid…

Vos films ont pour sujet la sexualité féminine …

Je ne trouve pas que j'explore la sexualité féminine. Je la dynamite. Je pose des questions à son sujet. Est-ce que c'est vraiment ce qu'on nous dit ? Exemple : la virginité. Jeune fille, j'entendais : « perdre sa virginité est un moment dont toute femme se souvient. » Et bien moi, pour ne pas vivre ça, j'ai tenu à la perdre avec un homme que je n'aimais pas. Pour n'y mettre aucun affect, que ça n'appartienne qu'à moi.

Pourquoi pensez-vous que vos films choquent ?

Ils suscitent surtout beaucoup de haine ! Si vous saviez tout ce que j'ai reçu comme signes de dégoûts et de haine, pour « 36 fillette ». Je pense que c'est parce que je suis dans une forme d'hyperréalisme, que je filme les choses frontalement et que, spectateur, on ne peut pas y échapper. Pour certains, ça fait mal. Paradoxalement, mes films sont vénérés dans le monde anglo-saxon, USA… Je suis adorée au Canada anglais, détestée au Québec. Les puritains m'adorent, les paillards gaulois me détestent…

Peut-on tout montrer ?

Disons qu'on ne doit rien s'interdire. Ce qu'on s'interdit, c'est par consensus. Un artiste doit repousser les limites. L'art se trouve entre les bornes et la limite. L'art est un acte politique. C'est répondre à des questions qui ne sont pas posées. Surtout dans le domaine de l'interdit.

Peut-on tout voir ?

Je pense que l'on peut tout voir, mais pas à n'importe quel moment… Je suis pour la censure pour les enfants, on doit les protéger. Pour des adultes, c'est différent. J'ai vu « Salo » de Pasolini, j'étais trop jeune. Insupportable. Je l'ai revu dix ans plus tard : un chef-d'œuvre.

Vous avez dit : « Le joli est affreux »…

Oui. Dire que quelque chose est joli, cela ne dérange pas. Le c'est ni beau ni laid, il n'y aucune transcendance. C'est ni Dieu ni diable, c'est rien, c'est comme le bon goût, ça ne dérange pas…

Catherine Breillat sera à l'ABC vendredi à 18 heures pour présenter « 36 fillette », à 20 heures à la Cinémathèque pour « Romance » et samedi, à 16 heures à la Cinémathèque pour « Une vieille maîtresse ».

CATHERINE BREILLAT RETROSPECTIVE : ALMOST MAINSTREAM

While her best films may still be more unconventional in style, in recent years Catherine Breillat has made a successful turn toward films that could almost be called mainstream while keeping the focus firmly on gender. The sexuality, while present, is slightly toned down in its explicitness. The storytelling is a bit more clearly drawn. These are the films one can watch to ease into Breillat’s filmography.Breillat has on multiple occasions explored the dynamic of a relationship between a teen girl and an older man. With 2001′s Brief Crossing, she reverses the dynamic as French teen Thomas meets British thirty-something Alice on a ferry across the English Channel. In many ways the film draws out the gender role reversal in this dynamic. The use of nudity is commendable in that, while Alice is certainly attractive, she does show those subtle signs of aging on her body.

2007′s The Last Mistress marks a real step up in terms of the cinematography and art direction relative to the grittier aesthetic through most of Breillat’s films to this point. This is fitting as Breillat leaves the realm of the modern setting for late 19th Century costume drama. The bulk of the film involves Ryno, a poor and somewhat disgraced man of aristocratic birth, relating the story of his past romance with Spanish siren Vellini to the grandmother of the wealthy woman he seeks to marry. He must earn her trust that he will be true to her granddaughter. Like many French films, love proves to be a wild and unkempt thing and drama ensues. The bulk of weddings and divorces and affairs makes for quite the whirlwind.

Fairy tales have always been rich ground for thematic subtext, but often, at least as presented by Disney, in a way that can be considered problematic on gender grounds. Breillat has turned to the world of fairy tales for her two most recent films, 2009′s Bluebeard and 2010′s The Sleeping Beauty. Bluebeard tells a story of two sisters who, due to their poverty, try to impress upon a nearby aristocrat seeking a wife. However, he is rumored to have killed all his previous wives. Like Fat Girl, the rivalry of sisters is of importance here in both parallel stories. The film has some interesting comments on patriarchy, though not as clearly drawn as might be desired.

Finally, The Sleeping Beauty is a story that has been critiqued on gender grounds because the female character is completely inert, asleep, waiting for a male to save her. Breillat puts a powerful twist by taking us into her dream world where she is the actor in the story. The princess is a fascinating character, initially insisting she is a boy and becoming upset by attempts to fold her into the gender norms. Early in her fantasy world when she is taken in by a mother, with one son, who always wanted a daughter, the princess is delighted by the hand-me-down boys clothes and playing along with her new brother in boys games. Then he hits puberty and once again gender is a source of tension. Ultimately, Breillat tells a tale about girls finding their own way toward being women.

Sex and Power: The Provocative Explorations of Catherine Breillat

The work of Catherine Breillat, the French filmmaker and novelist whose movies frequently explore the perversity animating male-female power dynamics in Western society, has always been fearlessly pertinent. These days, as more and more revelations about the sexual predations of high-profile men come to light, they may even be more pertinent.The Criterion Channel section of the streaming site Filmstruck recently unveiled its Catherine Breillat Collection, which offers all the movies the director has made in this century, with the exception of “Anatomy of Hell,” the 2004 movie about men’s fear of menstruation, and one of her most extreme works in terms of explicit content.

The first picture of the collection is the still-shocking “Fat Girl,” from 2001, which centers on a 12-year-old. Anaïs (Anaïs Reboux), chubby, pouty and red-cheeked, feels out of sorts while on holiday, watching her older sister, Elena (Roxane Mesquida), being romanced by a local Lothario, Fernando (Libero De Rienzo). The movie’s central jaw-dropper is a scene, about 20 minutes in, when Fernando visits the girls’ shared bedroom one night. A wide-awake Anaïs is witness to Fernando’s wheedling, inveigling “seduction” of Elena. When Elena instructs her beau to go only so far, he responds “I swear on my mother’s head.” Seconds later, Fernando says that he’s not sure if he can hold himself back and that it would be a shame if he had to go to another girl to get what he wants. And on it goes. It’s excruciating.

Not all of Ms. Breillat’s observations are specific to the vexation of women. This movie, and others of hers, feature intimate implications of the cosmic. I saw “Fat Girl” for the first time in 2001, at the Toronto International Film Festival. This is not quite a spoiler — because believe me, the scene in question is not one that you are going to see coming, even with this reveal — but the movie ends with the central character subjected to a mini-apocalypse: The world she knows ends before her eyes. It’s a shattering scene, constructed with an assurance that is kind of terrifying. On the day I saw the movie, Sept. 8, 2001, I found it too abrupt and arbitrary. Little did I know. Interviewing Ms. Breillat a couple of years later, I told her how my perception of the film changed after Sept. 11; her response was an enthusiastic nod of agreement — and a Gallic shrug.

All the other films in the collection are rich in wit, emotional tumult and philosophical trenchancy. “Sex Is Comedy,” from 2004, is a genuinely funny movie about moviemaking, inspired by the shooting of that startling sex scene from “Fat Girl.” Here Anne Parillaud plays a put-upon stand-in for Ms. Breillat. “The Last Mistress,” from 2008, is a 19th-century tale of a woman who refuses to take her lover’s rejection in stride. This movie’s subversions begin with the casting of a thoroughly modern screen presence, Asia Argento, in the title role.

There has often been a recognizable streak of fantasy in Ms. Breillat’s work, and in recent years she has given her tendencies in that direction freer rein by making films of well-known fairy tales. Her perspectives on “Bluebeard” (2010) and “Sleeping Beauty” (2011) are more than fractured; they are radical. Lola Créton, known in the United States mostly for her work in Mia Hansen-Love’s “Goodbye First Love” (2012) and Olivier Assayas’ “Something in the Air” (2013), gives a fierce performance in “Bluebeard” as Marie-Catherine, the title character’s clever young wife who is confounded by the temptation of a secret chamber in their shared castle.

The collection is completed by “Abuse of Weakness” (2014), Ms. Breillat’s most recent film, and possibly her greatest, so far. It’s a largely autobiographical account of catastrophic events after Ms. Breillat’s brain hemorrhage in 2004. (She also wrote a novel based on her experiences.)

In that film, Isabelle Huppert, in an even more astonishing performance than what she usually serves up, plays Maud, a writer and director we first see sliding out of her bed, half-paralyzed. Ms. Huppert portrays her suffering character, who remains partly paralyzed throughout, with incredible physicality. At times, Maud seems to masochistically luxuriate in her incapacitation. Watching television one evening, Maud is entranced by the bragging of a ruggedly handsome con man, recently released from prison and promoting a book about his swindles. She asks him to star in her next film; he agrees, and he almost immediately starts a psychological game with her.

“I don’t meet with my actors until I start filming,” Maud says, her left hand still crabbed from her stroke. Slumped in a chair opposite her, the con man, played by the French rapper Kool Shen, responds, “You are going to see a lot of me.” Soon Maud is writing him enormous checks and imperiously insisting to herself that she understands what’s going on and has some control over it. This is a subtle but unflinching psychological horror picture with a devastating finale.

If you’re in the mood to do more cinematic exploring, this month the cinephile site Filmatique, which specializes in international movies that normally get scant attention in the United States, focuses on North African directors and films. So far it has posted Mohcine Besri’s 2011 kidnapping drama, “The Miscreants”; Nadine Khan’s “Chaos, Disorder” (2013), a scrappy love triangle set in Cairo; and a female character study from 2012, “Coming Forth by Day,” from the Egyptian filmmaker Hala Lotfy.

On Dec. 22, the Tunisian picture “Challat of Tunis” debuts on the site. Directed by and featuring Kaouther Ben Hania, this mockumentary posits the existence of a criminal in prerevolutionary Tunisia called the Challat. (The word means blade in a Tunisian dialect.) In 2003, the movie tells us, he rampaged through Tunis on a motorbike, hunting down provocatively dressed women and slashing their buttocks with a straight razor.

The movie begins 10 years after, with Ms. Ben Hania trying to visit the prison where the Challat was supposedly held. Stymied, she goes to neighborhoods where he was reputed to have struck. Interviewing local residents, she finds men disparaging the Challat’s supposed victims and their scanty wear. They say things like “One must dress correctly. In a respectful fashion.” The movie teems with such upsetting, but not surprising, instances of victim-blaming. The filmmaker also interviews the maker of a “devout” video game in which the player is the Challat, and gains points for slashing inappropriately dressed women. If the player attacks a hijab-wearing woman, points are deducted. Ms. Ben Hania also explores the home life of a creepy braggart who claims to be the “real” Challat.

This is a satire that stings. The misogyny and threatened masculinity on display half a world away is no different from what exists in the United States; the only distinction is in the pretext. (Many of the men in this movie claim that their retrograde views are endorsed by Islam.) Like the films of Ms. Breillat, “Challat of Tunis” is uncomfortably timely.

DVD