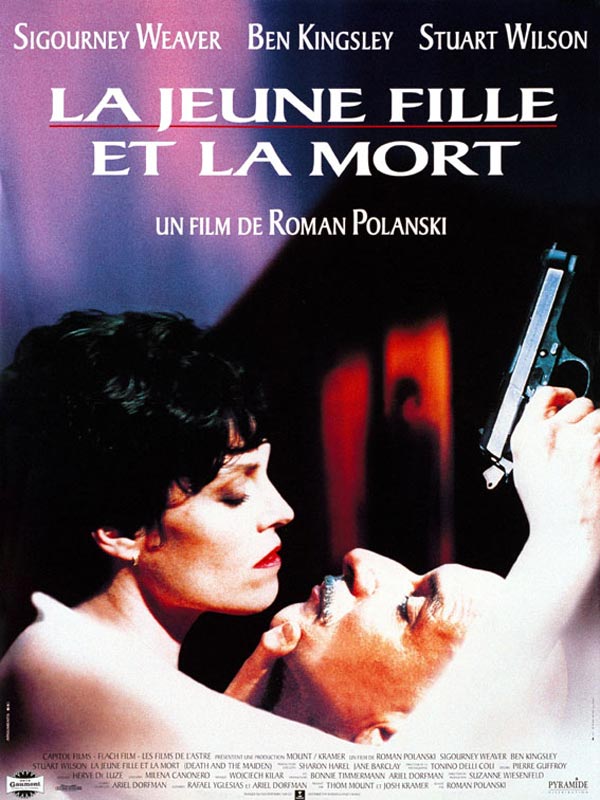

A Latin American republic in the early 1990s. Paulina Escobar is one of the countless victims of the military dictatorship that reigned over her country for several decades before giving way to a timorous and fragile democracy. Imprisoned, raped and tortured in the days when she was a militant with a student opposition newspaper, she still bears the physical and mental scars of this abuse and now lives in isolation with her husband Gerardo, a brilliant liberal militant courted by the new regime. Sickened by the idea that her torturers will never be brought to justice, Paulina bitterly reproaches Gerardo for having agreed to preside a puppet commission of inquiry into the junta's crimes.

When his car breaks down on a stormy night, Gerardo is given a lift by a courteous-looking man, Doctor Roberto Miranda, who brings him back to their country home. When this Good Samaritan returns to the house in the middle of the night for a futile reason, Paulina suddenly thinks that she recognizes the unctuous voice and the laugh of her torturer. Overcoming her fear, she takes the doctor's car where she finds a tape of Schubert's Death and the Maiden - the quartet that played each time she was raped. After pushing the vehicle off the top of a cliff, she returns to the house where she finds Miranda sleeping. She strikes him with a gun butt, gags him and ties him up.

Groggy, his face streaming with blood, the doctor protests angrily that he is innocent, claiming that he was in Spain at the time of the events. But Pauline refuses to listen both to his reasoning and to Gerardo's fearful objections. Holding sway over the two men, she attempts to make Miranda confess. Gerardo reluctantly accepts to play to role of the lawyer in this trial that soon becomes his. The verdict will be returned at dawn.

Réalisateur

REVUE DE PRESSE

interview de Roman Polanski concernant LA JEUNE FILLE ET LA MORT-626

FROM STAGE TO SCREEN Did you see "Death and the Maiden" on stage ? No. When I was first sent […]

interview de Roman Polanski concernant LA JEUNE FILLE ET LA MORT-626

FROM STAGE TO SCREEN

Did you see "Death and the Maiden" on stage ?

No. When I was first sent the text, Ariel Dorfman's play was on at the Royal Court Upstairs in London, where it was a big hit. It then transferred to the main theatre and the West End before finally being staged on Broadway, directed by Mick Nichols and starring Glenn Close, Gene Hackman and Richard Dreyfuss. The producer Thom Mount, with whom I had already worked on Pirates and Frantic, and his partner Bonnie Timmermann contacted me to adapt the play for the big screen. At one point, there was a possibility of staging it in Paris but I feared that would be too much.

"Death and the Maiden" scrupulously respect the three unities and has only three characters, in a single setting. Did that pose any particular problem ?

No, because the qualities of this play do not reside in its theatricality. The respect of the unities of time, place and action, as well as the length and density of the lines are not obstacles. I have always liked films in a enclosed setting; in fact, they gave me my first cinematic pleasure when the desire to become a director was born within me. Psychological films, atmospheric films have always interested me more than big spectacular productions. Even when I was young, I found nothing exciting about seeing ten thousand extras milling around on screen. I preferred an intimate setting: a simple bedroom, a hut, a boat... "Death and the Maiden" was a stimulating challenge. Many things about the project attracted me. The action had to be made "cinematic" without being opened up artificially, the three characters had to be brought to life, and moral considerations on guilt, responsibility, justice and the relativity of truth needed to be developed.

Rafael Yglesias, with whom you have written the final screenplay, feels that the play was more "political" than the film but that you have covered the couple's life and fraught relationship more completely.

That's right but everything depends on the way in which this play is staged. I heard that Mike Nichols presented a strictly apolitical reading of it. Yglesias and myself have favoured its philosophical dimension and universal nature by underplaying all the explicit references to Chilean history. At the same time, we need to root the action in a concrete setting to avoid any haziness or abstraction. Therefore, we continually thought of Chile while we were writing, then in designing the set, selecting the props, the radio jingles, etc. All that is perfectly authentic. The text, however, gives no geographic indications and the audience knows only that the action is set in a Latin American country.

The characters have Hispanic names: Paulina, Miranda, Gerardo, yet have no accent.

That would have made no sense; it would have been just as logical to have them speak Spanish! A couple of American critics seemed to regret that Sigourney Weaver, Ben Kingsley and Stuart Wilson didn't have a "Latino" physique. But South America isn't Mexico. In Chile or Argentina, you find people who look like us - blonds and redheads who could be French or Belgian. These countries aren't inhabited only by swarthy, moustachioed men! Even so, I remained hostile for some time to the idea of shooting an English-language film set in a land where people don't speak English. I would have had scruples about making a Polish peasant speak like that. But I changed my mind when I saw Schindler's List where that worked perfectly. After all, Hamlet doesn't speak in Danish!

THE CHARACTERS

Before tackling the film's moral aspect, let's talk about the couple formed by Paulina and Gerardo. Why is their relationship so

tense ?

There are two reasons for that: firstly, a deep-seated sense of guilt for Gerardo; and secondly, the trauma experienced by Paulina. But there are also very strong ties between them. They love each other in spite of everything.

Paulina demands the truth, she wants transparency and yet, until this night, she had never told Gerardo that she had been raped.

She told him about being tortured, not about the rape. As a lawyer and a defender of human rights, he knows very well how such "interrogations" unfold. But he finds it more fitting to overlook his in his wife's case.

Perhaps this blindness has the greatest negative effect on their relationship.

Yes, but Paulina has a share of responsibility in this misunderstanding all the same. She has conformed to the macho tradition and hasn't wanted to humiliate Gerardo by talking about it. She also thought that he must have suspected it.

And this artificial silence rots their relationship... Another grievance: Paulina reproaches Gerardo for going along with what she considers to be a fraud.

The commission that the new president has asked him to head will only investigate murders, not torture cases. Why? Because, before its collapse, the junta guaranteed its own protection and amnestied itself. Just as it did in Chile. And Paulina is sickened by the idea that her torturers will escape justice.

Paulina is the motor of the action. She launches the drama, sets up Miranda's interrogation by assuming a right of life and death over him. Can we say that she is pursuing a dual goal: re-establishing the truth and saving her marriage ?

No, her motivation is much more direct, much more of a gut reaction. She has a single obsession: revenge. If she had the time to think about it, she would see that it is also a kind of exorcism and re-appropriation of the self. But emotion gains the upper hand and there is clearly some urgency since this confrontation with Miranda is her last chance to be recognized as a victim and to express herself as a person.

When we discover her in this country house, we can immediately sense that she is incredibly anxious and we can't really imagine her taking part in her husband's public life.

She doesn't take part in it and, moreover, continually accuses Gerardo of compromising himself with the new authorities.

Why does Paulina lock herself in a cupboard? Out of fear, to punish herself or to return to the conditions of her imprisonment ?

For all those reasons but also because she feels safer there. She has a militant past; she has fought against the dictatorship as a student. She continues to be on her guard and she always has a weapon within reach...

THE CAST

Let's talk about the cast, staring with Sigourney Weaver.

She was the first actress who expressed the desire to play Paulina, while we were still at the pre-production stage. We were very interested, especially as her fame eased the financing of a potentially difficult undertaking. In the end, the whole project came together around Sigourney. Ben Kingsley came along much later. I was delighted that he wanted to play Miranda because he is really the kind of actor that we needed. Gene Hackman, who played the part in New York, is a great actor but I didn't want Miranda to have such an imposing physique. I wanted an ordinary man. Miranda isn't a brute, he was transformed by circumstances.

This choice is all the more remarkable because Ben Kingsley, while having the image of an "honest man", manages to suggest cunning and perversity with a simple shift in intonation or an almost imperceptible gleam in his eye...

We're a long way from Gandhi !

Audiences aren't so familiar with Stuart Wilson, who has ended up with the most ambiguous and complex character in Death and the Maiden.

Gerardo is probably the most difficult part to play in the film. I had seen Stuart Wilson in The Age of Innocence and I found both his performance and his physique interesting. Usually, he plays strong, insolent and macho characters. Here, he is constantly torn between two extremes. He is evolving all the time, playing judge and jury, husband, accused and prosecutor in turn. I find his performance surprising and original.

Miranda nonetheless remains the film's central mystery - a man of a perfectly respectable appearance about whom we continually wonder if he was a monster in the past...

Monsters rarely show their true colours. SS officers were sensitive and cultured people who loved Beethoven...

Does this mean that we are all potential torturers ?

I'd rather not give an opinion on the profound nature of mankind. Is each one of us likely to change in certain conditions? That would be too terrifying to imagine and, as far as I'm concerned, I can't really see myself as a torturer. I rather tend to think that good and evil coexist in each man to varying degrees but that good always triumphs in the end. Otherwise, we wouldn't be here.

Does a country that has been guilty of crimes against humanity require a collective self-examination or should it let time do its work and stake its future on forgetfulness ?

The first thing needed is awareness and then reconciliation. But no one must forget, even if it's had to believe that a civilized country can sink into barbarity like France in the time of the Terror and the guillotines.

THE SHOOT

You had three remarkable actors at your disposal who had to confront each other permanently over several weeks, in a single setting. How did you get them into condition ?

Once the set had been built, I was lucky enough to be able to rehearse the whole film with the actors, the script supervisor, the assistant director and the props man. This was important for continuity because a large number of props (lamp, electric wire, knife, adhesive tape, etc.) had to be precisely located in order to intervene at key points in the action. Another advantage: we shot in chronological order which allowed the actors to model their character day by day, in a totally natural manner. The fact of having been able to "run through" the script and then film it like this was a help to us all.

The film is full of physical details and gestures that give it a great deal of truth: the way in which Paulina presses against Miranda to wake him, the fact that she walks nearly all the time barefoot...

These are details that we found during the rehearsals. But there were already a large number in the screenplay since I always try to play out the scenes as we write.

What was the atmosphere on the set like ?

It was very intense but extremely gratifying since I was dealing with real professionals. The productions was well organized and I had a remarkable crew.

The film plays on such fine distinctions and the work of the actors is so precise that it must have been hard at times to choose between two takes.

We faced this problem from the very first scene when we discover Paulina framed in the window. Should she be nervous or relaxed? How should she react to the news bulletin? Was it necessary to highlight the knife that she was using to carve the chicken? We never stopped asking ourselves this kind of question, fine-tuning and dosing the effects.

Tell us something about your work with Pierre Guffroy and Tonino Delli Colli

As usual, I made sketches to locate the action in a precise geographic setting, corresponding to my particular needs as the film's director. We had to sense the proximity of the sea, be at the end of a road running along the cliffs, have an unimpeded view, etc. We had to determine all these parameters, inscribe them in a concrete setting, then build the same house in Spain for the exterior shots. I also told Pierre Guffroy my ideas concerning the layout of the house. He studied, adapted and reworked all that to make the set easier to build. All the partitions were removable, of course, given the cramped nature of such settings as the kitchen, toilet, cupboard or bathroom.

Another wager: a large part of the film takes place during a power failure.

Tonino has done excellent work. I wanted realistic lighting, but candles and paraffin lamps don't light a great deal and that was likely to become very tiring for the audience. We had to find a compromise, create an atmosphere that was neither artificial nor challenging. He pulled this off remarkably.

The exteriors are amazing: the leaden sky looks more like a backdrop than the rest of the film and is just as oppressive.

We had to shoot these scenes in the same style; we wanted to make sure that there was no break in the style.

MORALITY AND POLITICS

Let us return to the three characters. Rafael Yglesias points out a paradox: Gerardo is right on a political level since a clean sweep must be made and civil peace re-established but he is wrong on a private level whereas Paulina is right on the private level but wrong on the political one.

I agree with that way of putting it. I think it is also interesting that the characters should be led to reveal extremely contradictory facets of themselves: Miranda, of course, but also Paulina who may appear totally irrational and uncontrollable but who ends up controlling the whole situation; Gerardo, the humanist lawyer, who actually comes to accept the idea of eliminating Miranda...

Sigourney Weaver says: "I'm sure that Roman wants the audience to identify with each of the protagonists in turn."

That's right. Our sympathies go from one to the other; our convictions fluctuate throughout the film.

How do you explain Paulina's reaction after Miranda's final monologue ?

I wanted a realistic ending. And in everyday life, you don't easily kill someone, even if they've hurt you. I couldn't see a woman like her pushing this man off the cliff. I don't even think she ever intended to kill him.

So the trial was just a sham, psychological torture to make him break down ?

Yes. And once she gets what she wants, the rest doesn't matter.

And the last look that they exchange at the concert? Miranda has pulled through; like most of the men like him. No punishment would have been worthy of the damage that he did her. What punishment could Paulina have given him ? Electrocute him, sodomize him ? Have him thrown in jail ?

He'd be released sooner or later and she'd meet him on her path again. It's a fact that cannot be avoided. You have to learn to live with it...

Did you see "Death and the Maiden" on stage ?

No. When I was first sent the text, Ariel Dorfman's play was on at the Royal Court Upstairs in London, where it was a big hit. It then transferred to the main theatre and the West End before finally being staged on Broadway, directed by Mick Nichols and starring Glenn Close, Gene Hackman and Richard Dreyfuss. The producer Thom Mount, with whom I had already worked on Pirates and Frantic, and his partner Bonnie Timmermann contacted me to adapt the play for the big screen. At one point, there was a possibility of staging it in Paris but I feared that would be too much.

"Death and the Maiden" scrupulously respect the three unities and has only three characters, in a single setting. Did that pose any particular problem ?

No, because the qualities of this play do not reside in its theatricality. The respect of the unities of time, place and action, as well as the length and density of the lines are not obstacles. I have always liked films in a enclosed setting; in fact, they gave me my first cinematic pleasure when the desire to become a director was born within me. Psychological films, atmospheric films have always interested me more than big spectacular productions. Even when I was young, I found nothing exciting about seeing ten thousand extras milling around on screen. I preferred an intimate setting: a simple bedroom, a hut, a boat... "Death and the Maiden" was a stimulating challenge. Many things about the project attracted me. The action had to be made "cinematic" without being opened up artificially, the three characters had to be brought to life, and moral considerations on guilt, responsibility, justice and the relativity of truth needed to be developed.

Rafael Yglesias, with whom you have written the final screenplay, feels that the play was more "political" than the film but that you have covered the couple's life and fraught relationship more completely.

That's right but everything depends on the way in which this play is staged. I heard that Mike Nichols presented a strictly apolitical reading of it. Yglesias and myself have favoured its philosophical dimension and universal nature by underplaying all the explicit references to Chilean history. At the same time, we need to root the action in a concrete setting to avoid any haziness or abstraction. Therefore, we continually thought of Chile while we were writing, then in designing the set, selecting the props, the radio jingles, etc. All that is perfectly authentic. The text, however, gives no geographic indications and the audience knows only that the action is set in a Latin American country.

The characters have Hispanic names: Paulina, Miranda, Gerardo, yet have no accent.

That would have made no sense; it would have been just as logical to have them speak Spanish! A couple of American critics seemed to regret that Sigourney Weaver, Ben Kingsley and Stuart Wilson didn't have a "Latino" physique. But South America isn't Mexico. In Chile or Argentina, you find people who look like us - blonds and redheads who could be French or Belgian. These countries aren't inhabited only by swarthy, moustachioed men! Even so, I remained hostile for some time to the idea of shooting an English-language film set in a land where people don't speak English. I would have had scruples about making a Polish peasant speak like that. But I changed my mind when I saw Schindler's List where that worked perfectly. After all, Hamlet doesn't speak in Danish!

THE CHARACTERS

Before tackling the film's moral aspect, let's talk about the couple formed by Paulina and Gerardo. Why is their relationship so

tense ?

There are two reasons for that: firstly, a deep-seated sense of guilt for Gerardo; and secondly, the trauma experienced by Paulina. But there are also very strong ties between them. They love each other in spite of everything.

Paulina demands the truth, she wants transparency and yet, until this night, she had never told Gerardo that she had been raped.

She told him about being tortured, not about the rape. As a lawyer and a defender of human rights, he knows very well how such "interrogations" unfold. But he finds it more fitting to overlook his in his wife's case.

Perhaps this blindness has the greatest negative effect on their relationship.

Yes, but Paulina has a share of responsibility in this misunderstanding all the same. She has conformed to the macho tradition and hasn't wanted to humiliate Gerardo by talking about it. She also thought that he must have suspected it.

And this artificial silence rots their relationship... Another grievance: Paulina reproaches Gerardo for going along with what she considers to be a fraud.

The commission that the new president has asked him to head will only investigate murders, not torture cases. Why? Because, before its collapse, the junta guaranteed its own protection and amnestied itself. Just as it did in Chile. And Paulina is sickened by the idea that her torturers will escape justice.

Paulina is the motor of the action. She launches the drama, sets up Miranda's interrogation by assuming a right of life and death over him. Can we say that she is pursuing a dual goal: re-establishing the truth and saving her marriage ?

No, her motivation is much more direct, much more of a gut reaction. She has a single obsession: revenge. If she had the time to think about it, she would see that it is also a kind of exorcism and re-appropriation of the self. But emotion gains the upper hand and there is clearly some urgency since this confrontation with Miranda is her last chance to be recognized as a victim and to express herself as a person.

When we discover her in this country house, we can immediately sense that she is incredibly anxious and we can't really imagine her taking part in her husband's public life.

She doesn't take part in it and, moreover, continually accuses Gerardo of compromising himself with the new authorities.

Why does Paulina lock herself in a cupboard? Out of fear, to punish herself or to return to the conditions of her imprisonment ?

For all those reasons but also because she feels safer there. She has a militant past; she has fought against the dictatorship as a student. She continues to be on her guard and she always has a weapon within reach...

THE CAST

Let's talk about the cast, staring with Sigourney Weaver.

She was the first actress who expressed the desire to play Paulina, while we were still at the pre-production stage. We were very interested, especially as her fame eased the financing of a potentially difficult undertaking. In the end, the whole project came together around Sigourney. Ben Kingsley came along much later. I was delighted that he wanted to play Miranda because he is really the kind of actor that we needed. Gene Hackman, who played the part in New York, is a great actor but I didn't want Miranda to have such an imposing physique. I wanted an ordinary man. Miranda isn't a brute, he was transformed by circumstances.

This choice is all the more remarkable because Ben Kingsley, while having the image of an "honest man", manages to suggest cunning and perversity with a simple shift in intonation or an almost imperceptible gleam in his eye...

We're a long way from Gandhi !

Audiences aren't so familiar with Stuart Wilson, who has ended up with the most ambiguous and complex character in Death and the Maiden.

Gerardo is probably the most difficult part to play in the film. I had seen Stuart Wilson in The Age of Innocence and I found both his performance and his physique interesting. Usually, he plays strong, insolent and macho characters. Here, he is constantly torn between two extremes. He is evolving all the time, playing judge and jury, husband, accused and prosecutor in turn. I find his performance surprising and original.

Miranda nonetheless remains the film's central mystery - a man of a perfectly respectable appearance about whom we continually wonder if he was a monster in the past...

Monsters rarely show their true colours. SS officers were sensitive and cultured people who loved Beethoven...

Does this mean that we are all potential torturers ?

I'd rather not give an opinion on the profound nature of mankind. Is each one of us likely to change in certain conditions? That would be too terrifying to imagine and, as far as I'm concerned, I can't really see myself as a torturer. I rather tend to think that good and evil coexist in each man to varying degrees but that good always triumphs in the end. Otherwise, we wouldn't be here.

Does a country that has been guilty of crimes against humanity require a collective self-examination or should it let time do its work and stake its future on forgetfulness ?

The first thing needed is awareness and then reconciliation. But no one must forget, even if it's had to believe that a civilized country can sink into barbarity like France in the time of the Terror and the guillotines.

THE SHOOT

You had three remarkable actors at your disposal who had to confront each other permanently over several weeks, in a single setting. How did you get them into condition ?

Once the set had been built, I was lucky enough to be able to rehearse the whole film with the actors, the script supervisor, the assistant director and the props man. This was important for continuity because a large number of props (lamp, electric wire, knife, adhesive tape, etc.) had to be precisely located in order to intervene at key points in the action. Another advantage: we shot in chronological order which allowed the actors to model their character day by day, in a totally natural manner. The fact of having been able to "run through" the script and then film it like this was a help to us all.

The film is full of physical details and gestures that give it a great deal of truth: the way in which Paulina presses against Miranda to wake him, the fact that she walks nearly all the time barefoot...

These are details that we found during the rehearsals. But there were already a large number in the screenplay since I always try to play out the scenes as we write.

What was the atmosphere on the set like ?

It was very intense but extremely gratifying since I was dealing with real professionals. The productions was well organized and I had a remarkable crew.

The film plays on such fine distinctions and the work of the actors is so precise that it must have been hard at times to choose between two takes.

We faced this problem from the very first scene when we discover Paulina framed in the window. Should she be nervous or relaxed? How should she react to the news bulletin? Was it necessary to highlight the knife that she was using to carve the chicken? We never stopped asking ourselves this kind of question, fine-tuning and dosing the effects.

Tell us something about your work with Pierre Guffroy and Tonino Delli Colli

As usual, I made sketches to locate the action in a precise geographic setting, corresponding to my particular needs as the film's director. We had to sense the proximity of the sea, be at the end of a road running along the cliffs, have an unimpeded view, etc. We had to determine all these parameters, inscribe them in a concrete setting, then build the same house in Spain for the exterior shots. I also told Pierre Guffroy my ideas concerning the layout of the house. He studied, adapted and reworked all that to make the set easier to build. All the partitions were removable, of course, given the cramped nature of such settings as the kitchen, toilet, cupboard or bathroom.

Another wager: a large part of the film takes place during a power failure.

Tonino has done excellent work. I wanted realistic lighting, but candles and paraffin lamps don't light a great deal and that was likely to become very tiring for the audience. We had to find a compromise, create an atmosphere that was neither artificial nor challenging. He pulled this off remarkably.

The exteriors are amazing: the leaden sky looks more like a backdrop than the rest of the film and is just as oppressive.

We had to shoot these scenes in the same style; we wanted to make sure that there was no break in the style.

MORALITY AND POLITICS

Let us return to the three characters. Rafael Yglesias points out a paradox: Gerardo is right on a political level since a clean sweep must be made and civil peace re-established but he is wrong on a private level whereas Paulina is right on the private level but wrong on the political one.

I agree with that way of putting it. I think it is also interesting that the characters should be led to reveal extremely contradictory facets of themselves: Miranda, of course, but also Paulina who may appear totally irrational and uncontrollable but who ends up controlling the whole situation; Gerardo, the humanist lawyer, who actually comes to accept the idea of eliminating Miranda...

Sigourney Weaver says: "I'm sure that Roman wants the audience to identify with each of the protagonists in turn."

That's right. Our sympathies go from one to the other; our convictions fluctuate throughout the film.

How do you explain Paulina's reaction after Miranda's final monologue ?

I wanted a realistic ending. And in everyday life, you don't easily kill someone, even if they've hurt you. I couldn't see a woman like her pushing this man off the cliff. I don't even think she ever intended to kill him.

So the trial was just a sham, psychological torture to make him break down ?

Yes. And once she gets what she wants, the rest doesn't matter.

And the last look that they exchange at the concert? Miranda has pulled through; like most of the men like him. No punishment would have been worthy of the damage that he did her. What punishment could Paulina have given him ? Electrocute him, sodomize him ? Have him thrown in jail ?

He'd be released sooner or later and she'd meet him on her path again. It's a fact that cannot be avoided. You have to learn to live with it...