Réalisateur

REVUE DE PRESSE

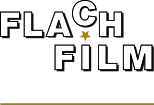

BLUEBEARD/BARBE BLEUE

Having built a career on provocative, sexually explicit yet cerebral fare ("Romance," "Sex Is Comedy"), Catherine Breillat shocked auds with her 2007 period piece, "The Last Mistress," because it was not all that shocking. Now the Gallic helmer's latest, "Bluebeard," features considerable blood but no sex.

BLUEBEARD

Using a lively and much younger female cast than usual, Breillat makes a pointed - and one suspects, quasi-autobiographical – comment on girlhood, its dreams and rebellious impulses. Boasting a Depardieu-scale bulk and looming menace, Thomas's ogre-husband is at once baleful and charming.

FLACH FILM adapte des contes populaires pour ARTE

La société de production de Jean-François Lepetit a produit le Barbe Bleue, de Catherine Breillat. Le film, qui avait été présenté au Festival de Berlin en février dernier, sera diffusé sur Arte le 6 octobre prochain.

Barbe Bleue

Extrait du 6/10/09 “Le Barbe Bleue de Catherine Breillat fait dialoguer avec un rare éclat mythologie intime et légende populaire” […]

False security of Wealth : a tale turns cautionary

In “Bluebeard,” a sly rethink of the freakily morbid fairy tale, the filmmaker Catherine Breillat makes the case that once-upon-a-time stories never end. Divided into two parallel narratives — one focuses on Bluebeard and his dangerously curious wife, while the other involves two little girls in the modern era revisiting the tale — the movie is at once direct, complex and peculiar.

Fairy-Tale Endings : Death by Husband

“When I was growing up in the 1950s, it was a fairy tale that was specifically aimed at little girls,” said the French director Catherine Breillat, 61, whose film adaptation of the tale opened in New York on Friday. “I found it very strange that in the end it’s about teaching little girls to love a man who will kill them. Because that is the story that it tells.”

After the Wedding Bells Comes the Drama for the Wife of Bluebeard

sychologically rich, unobtrusively minimalist, at once admirably straightforward and slyly comic, Catherine Breillat's Bluebeard is a lucid retelling and simultaneous explanation of Charles Perrault's nastiest, most un-Disneyfiable nursery story.

Q&A with Bluebeards Catherine Breillat

With Bluebeard, Catherine Breillat—perhaps the most willful feminist provocatrice in cinema today—slyly subverts Charles Perrault's gruesome fairy tale about a young bride married to an aristocrat who has murdered his previous wives.

BLUEBEARD/BARBE BLEUE

(France) A Flach Film, CB Films, Arte France presentation. (International sales: Pyramide Intl., Paris.) Produced by Jean-Francois Lepetit, Sylvette Frydman. Directed, written by Catherine Breillat.With: Dominique Thomas, Lola Creton, Daphne Baiwir, Marilou Lopes-Benites, Lola Giovannetti, Farida Khelfa, Isabelle Lapouge.

Having built a career on provocative, sexually explicit yet cerebral fare ("Romance," "Sex Is Comedy"), Catherine Breillat shocked auds with her 2007 period piece, "The Last Mistress," because it was not all that shocking. Now the Gallic helmer's latest, "Bluebeard," features considerable blood but no sex. This offbeat but compelling take on the tale, arguably the first serial-killer yarn, emphasizes sisterly bonds but still gets to the original story's heart of mysterious darkness with impressive results. Low-budget production values will, however, keep pic locked up in arthouse ivory towers.

Once upon a time in the 1950s, somewhere in France, two young sisters, 7-or-so-year-old Catherine (Marilou Lopes-Benites) and Marie-Anne (Lola Giovannetti), who's a couple years older, go to play in the attic. Impish Catherine insists on reading "Bluebeard" to her frightened sister, and as she does, the story unfolds onscreen.

Set in an unspecific time that looks roughly like the early 18th century, pic introduces two other sisters, teenagers Anne (Daphne Baiwir) and the younger Marie-Catherine (Lola Creton), being thrown out of a nun-run boarding school when their father dies and their family is unable to afford the school fees. Back home, the girls watch as the furniture is taken away to pay bills.

With no dowry to offer, the chance to become a bride to the notorious local squire Bluebeard (Dominique Thomas), who'll take a wife with no cash down, starts to look attractive. The only hitch is that his previous wives had a habit of never being seen again.

Nevertheless, Marie-Catherine is literally and figuratively hungry for the good life and agrees to marry Bluebeard, finding him surprisingly gentle at home. He only asks that she obey a single rule: Don't open the one room he forbids her to enter while he's away. Everyone knows what happens next, although there's still a twist in store.

Although the script is roughly faithful to author Charles Perrault's original tale, there's no mistaking that this is a Catherine Breillat film. Characters talk in that slightly stiff, declamatory way they always do in her films, sisters love and hate each other in the same instant (invoking shades of "Fat Girl"), and relations between the sexes are fraught with mutual incomprehension and disappointment. And yet, despite the chamber of horror that reps the pic's climactic reveal, the tone is dreamy, almost breezy, with the childish banter between the two 1950s girls even offering light relief.

Having said that, prospective distribs are hardly likely to market this to family auds, although Breillat perfectly understands how kids, especially girls, crave stories that terrify them. In fact, in the film's press notes, she writes about the autobiographical inspiration for the story.

Shot on HD, pic clearly cut corners in various craft departments, such as costume and sets. Several times, Breillat even uses exactly the same shot of a character going up or down a set of stairs two or three times in a row to suggest the staircase is longer than it really is, although this might have been a deliberate device.

Camera (color, HD), Vilko Filac; editor, Pascale Chavance; set designer, Olivier Jacquet; costume designer, Rose-Marie Melka; sound (Dolby Digital), Yves Osmu. Reviewed at Berlin Film Festival (Panorama), Feb. 8, 2009. Running time: 78 MIN.

Leslie Felperin February - 09, 2009

BLUEBEARD

For once, the sexual content in a Catherine Breillat is implicit instead of wildly in-your-face, but otherwise, offbeat fairy-tale venture Bluebeard (Barbe-Bleue) bears the unmistakable stamp of the veteran French provocatrice. An austere, low-budget video-shot venture, this quietly surreal Freudian fable is an elegant exercise of style with a sly humorous undertow. While revealing no radically new vision, thematically or cinematically, the film is distinctive enough to keep Breillat followers happy, and upmarket niche sales should be healthy while festivals come queuing.It's no surprise that Breillat would attempt a feminist take on the grisly tale of Bluebeard, which British novelist Angela Carter very much made her own: while there's no explicit sourcing here of Carter's rewrite (in her 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber), it's surely an implicit reference. A parable of male power and female sexual knowledge, Breillat's version of the story is primarily set – judging by the wardrobe – in 16th-century France. It begins with two adolescent girls, Marie-Catherine (Creton) and reputed 'bad seed' younger sister Anne

(Baiwir), being sent home from their convent school when their father dies. There seem few prospects for the newly impoverished girls, until news comes that local baron Barbe-Bleue (Thomas) is looking for a bride. He is reputed to be both ugly and dangerous, but defiant Anne, chosen to marry him, is game for anything and proves an unflappable match for the

hefty, hirsute Bluebeard.

The Bluebeard story itself is followed along traditional lines, while in a parallel thread, the Charles Perrault version of the tale is read, possibly in the present day, by a much younger pair of siblings, Marie-Anne and Catherine (Giovannetti, Lopes-Benites). Part of the fun in this mischievous mirroring lies in the comic gloss that the latter sisters put on the story and on adult sexuality, especially when the young Lopes-Benites, possibly improvising, offers her own bizarre theories about what marriage entails.

The film's great surprise is its austere restraint, the most shocking moment coming when the little Lopes-Benites takes the older Baïwir's place as Barbe-Bleue's bride confronts the charnel-house horrors of his locked room. Another shock comes right at the end, and it is typical of Breillat's mischief that it involves a character we hardly expect to get into trouble.

Using a lively and much younger female cast than usual, Breillat makes a pointed - and one suspects, quasi-autobiographical – comment on girlhood, its dreams and rebellious impulses. Boasting a Depardieu-scale bulk and looming menace, Thomas's ogre-husband is at once baleful and charming.

Blue Beard is a small-scale follow-up to the torrid costume-drama flourish of Breillat's The Last Mistress, but it shows the director on her most controlled cerebral form, even in this minor key.

Production companies

Flach Film

CB Films

ARTE France

International sales

Pyramide International

(33) 1 42 96 02 20

Producers

Jean-François Petit

Sylvette Frydman

Cinematography

Vilko Filac

Production design

Olivier Jacquet

Editor

Pascal Chavance

Main cast

Dominique Thomas

Lola Creton

Daphné Baïwir

Marilou Lopes-Benites

Lola Giovannetti

Jonathan Romney - February 9, 2009

FLACH FILM adapte des contes populaires pour ARTE

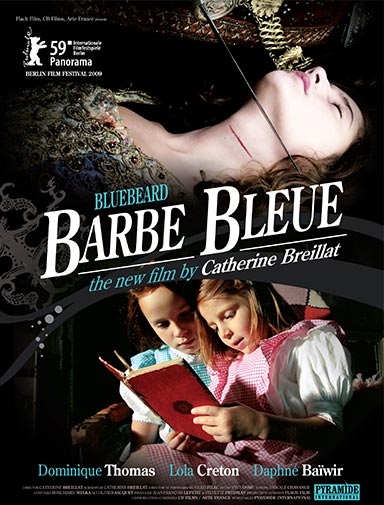

Ecran Total du 24/09/2009La société de production de Jean-François Lepetit a produit le Barbe Bleue, de Catherine Breillat. Le film, qui avait été présenté au Festival de Berlin en février dernier, sera diffusé sur Arte le 6 octobre prochain. Dans la foulée de Barbe Bleue, Flach-Film –dont le département télévision est dirigé par Sylvette Frydman- développe une collection de libres adaptations de contes populaires par des réalisateurs de notoriété, pour Arte. Un premier projet est d’ores et déjà en cours d’écriture : La Belle au bois dormant, dont la mise en scène sera assurée par Catherine Breillat.

Le Film Français du 25/09/2009

Flach Film veut revisiter Les contes populaires pour Arte

Alors que Barbe Bleue de Catherine Breillat, présenté avec succès à la dernière Berlinade, sera diffusé sur Arte le mardi 6 octobre, Flach Film développe une collection pour la chaîne franco-allemande portant à l’écran des adaptations libres de contes populaires par différents réalisateurs connus.

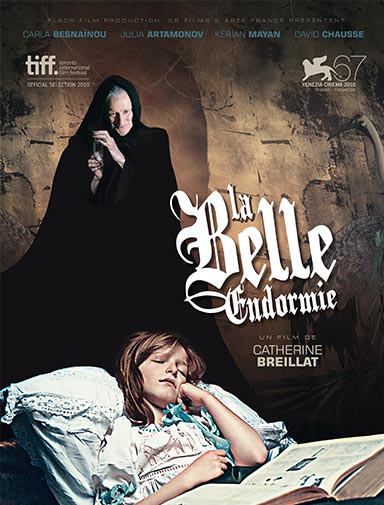

Déjà en cours d’écriture, La Belle au bois dormant sera lui aussi réalisé par Catherine Breillat. Le tournage doit commencer début 2010. Pour Jean-François Lepetit, le créateur de Flach Film, « l’idée est d’adapter de façon contemporaine des contes qui résonnent dans l’imaginaire collectif ». Ces films seront, dotés d’un budget d’environ 1,2M€ chacun, aussi bien destinés à la télé (Arte) qu’au cinéma. Ainsi, Barbe Bleue sortira en salle en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis. Pour la suite, Jean-François Lepetit évoque les noms de Jacques Doillon ou Marina de Van à la mise en scène.

Barbe Bleue

Extrait du 6/10/09

"Le Barbe Bleue de Catherine Breillat fait dialoguer avec un rare éclat mythologie intime et légende populaire" - Nathalie Dray

False security of Wealth : a tale turns cautionary

In “Bluebeard,” a sly rethink of the freakily morbid fairy tale, the filmmaker Catherine Breillat makes the case that once-upon-a-time stories never end. Divided into two parallel narratives — one focuses on Bluebeard and his dangerously curious wife, while the other involves two little girls in the modern era revisiting the tale — the movie is at once direct, complex and peculiar. It isn’t at all surprising that Ms. Breillat, a singular French filmmaker with strong, often unorthodox views on women and men and sex and power, would have been interested in a troubling tale about the perils of disobedient wives. Ms. Breillat never behaves.

That unruliness can be thrilling in films like “A Real Young Girl,” “Perfect Love,” “Romance,” “Fat Girl” and “The Last Mistress,” with their intellectually provoking, intemperate and gutsy cinematic explorations of female desire. Some are shocking, though less because they sometimes include depictions of real and feigned sex. While it’s unusual to see a woman filmmaker (even a French one) outside of pornography let loose with such unvarnished, bold, even grotesque images, what makes you squirm with embarrassment, delight, nervousness, shame, guilt, pleasure or displeasure (seeing is feeling), aren’t the orifices and the tumescence. It’s that she has dared to put the often unarticulated and generally unrepresented on screen, where everyone can see them. She makes the invisible, women included, visible.

Ms. Breillat’s most audacious move in “Bluebeard,” an unthrilling if still pungent work, comes at the level of form, in the bifurcated way she tells her story. Certainly Ms. Breillat suggests that this is very much her — and every other woman’s — story, despite (perhaps because of) its provenance. The original was written by Charles Perrault (1628-1703), whose contributions to fairy tales are so influential — he wrote down folk tales, giving them shape — Disney should pay his heirs royalties. More than a century before the Brothers Grimm, Perrault staked a claim on the female imagination in particular with “Cinderella,” “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Sleeping Beauty.” He had a thing for girls and women in trouble, making Ms. Breillat a good match.

“Bluebeard” suits Ms. Breillat, who likes to mix the blunt in with the oblique. The story involves an aristocrat (Dominique Thomas) with a number of mysteriously missing wives who takes a new bride, Marie-Catherine (Lola Creton). One day, before leaving on a trip, he hands over his keys, telling her that she can enter all the rooms save one. But after he leaves, she unlocks the forbidden chamber — the wife must defy him for the tale to exist — where she discovers the putrid bodies of his other wives hanging like meat. Meanwhile, the two little girls (Marilou Lopes-Benites and Lola Giovannetti) keep popping in and out of the movie, one reading the story of “Bluebeard” enthusiastically as the other blanches and recoils in horror.

The little girls are naturals and the dusty attic in which they read and play looks genuine enough to sneeze at. Not so the actors in the Bluebeard section, who move in period costumes through minimalist sets that have little of the sumptuous detail that tends to characterize more mainstream and costly efforts of this type. There’s a stripped-down quality to these trappings, which might be a function of budgetary constraints but also complements Ms. Breillat’s analytic approach, the critical distance she sometimes likes to assume. The sets, the clothes, the telegraphed performances — actors recite lines that sound like lines — along with the intermittent annotations from the little girls, remind you that you’re watching a self-conscious fiction, one that generations have preserved and recast.

The movie, which was shot in digital that often looks too flimsy for Ms. Breillat’s big ideas (you might think of Cocteau’s “Beauty and the Beast” with a sigh), opens in a convent with Marie-Catherine and her older sister, Anne (Daphné Baïwir), hearing of their father’s death. Anne weeps while Marie-Catherine rages, and together, newly impoverished, they leave. On their journey home Marie-Catherine sees a castle, and vows to live in one, then learns that it belongs to Bluebeard. She ends up in one after all. But before she does, Ms. Breillat, in a needless scene, shows a servant beheading a fowl, the camera lingering on its twitching body. Ah, yes, someone’s goose, having been killed, will surely be cooked — but whose?

The answer to that question proves more thoughtful than that crude image of the bird suggests. The British writer Angela Carter characterized Perrault’s fairy tales as nursery tales that have been “purposely dressed up as fables of the politics of experience.” Ms. Carter, who rewrote classic fairy tales to her own feminist ends, including a version of “Bluebeard” that she titled “The Bloody Chamber,” was interested in how they turn experience into stories, particularly in respect to gender. It seems probable that Ms. Breillat is familiar with Ms. Carter: the little girls in this screen revision, for instance, are dressed in gingham, which is what the heroine of “The Bloody Chamber” wears before she marries the wealthy man she doesn’t love.

All fairy tales have morals and the one in Ms. Breillat’s “Bluebeard” is brutal, suitably bloody and, like all good retellings, both similar to and different from earlier iterations. Like Ms. Carter, Ms. Breillat does not let women off easy: they are rarely if ever simply (or simple) victims. And to see Marie-Catherine as purely Bluebeard’s victim is to forget that she has a part in how the story not only ends, but also how it develops, for good and for bad. For her part, Ms. Breillat narrates the fairy tale three ways: in the period story, through the little girls and, finally, through the overall film. None are fully satisfying, but together they offer a sharp, knowing gloss on how our stories define who we were and who we become.

BLUEBEARD

Opens on Friday in Manhattan.

Written and directed by Catherine Breillat, based on the tale by Charles Perrault; director of photography, Vilko Filac; edited by Pascale Chavance; sets by Olivier Jacquet; costumes by Rose-Marie Melka; produced by Jean-François Lepetit and Sylvette Frydman; released by Strand Releasing. At the IFC Center, 323 Avenue of the Americas, at Third Street, Greenwich Village. In French, with English subtitles. Running time: 1 hour 20 minutes. This film is not rated.

WITH: Dominique Thomas (Barbe Bleue), Lola Creton (Marie-Catherine), Daphné Baïwir (Anne), Marilou Lopes-Benites (Catherine), Lola Giovannetti (Marie-Anne), Farida Khelfa (Mother Superior) and Isabelle Lapouge (Mother).

Manohla Dargis

http://movies.nytimes.com/2010/03/26/movies/26bluebeard.html?ref=movies

Fairy-Tale Endings : Death by Husband

Paris

THERE once lived a hideously blue-bearded man who slit the throats of his half-dozen wives, stashing their corpses in the basement of his castle one by one. So goes the legendary folk tale “Bluebeard” (“La Barbe Bleue”), published by Charles Perrault in 1697 to become an enduring European bedtime story.

“When I was growing up in the 1950s, it was a fairy tale that was specifically aimed at little girls,” said the French director Catherine Breillat, 61, whose film adaptation of the tale opened in New York on Friday. “I found it very strange that in the end it’s about teaching little girls to love a man who will kill them. Because that is the story that it tells.”

In this Prince Charming-free cautionary tale, marriage is not a happy end but a point of departure. As the story goes, Bluebeard (Dominique Thomas), a man with a reputation for misplacing his many wives, entrusts his newest bride (Lola Créton) with a key to a forbidden door and then leaves on a business trip. During his absence curiosity inevitably gets the best of her, and when she unlocks the door, she discovers a macabre collection of her husband’s ex-wives. The key, tainted with mysteriously fresh blood, betrays her disobedience, and Bluebeard condemns her to join his other spouses. But this time the new wife buys a bit of time by requesting a last prayer and is saved by a pair of sword-wielding men.

There are dozens of versions of the Bluebeard tale, including “Fitcher’s Bird” as told by the Brothers Grimm. Perrault’s “Bluebeard” was influenced partly by the real-life story of Gilles de Rais, a 15th-century pedophile and child murderer, and the word bluebeard is now shorthand for “serial killer.”

The character’s shadowy presence has long haunted works of art, music and literature the world over. He makes an appearance in Stephen King’s novel “The Shining”; Kurt Vonnegut used the story as a partial premise for his “Bluebeard,” a best-selling 1987 novel; Humbert Humbert compares himself to the character in Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita.” The specter of Bluebeard has also inspired operas by Bela Bartok and Jacques Offenbach and turns up in an untitled 1917 sonnet from the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Yet Bluebeard doesn’t have the name recognition of a Cinderella or Little Red Riding Hood in the United States, and its dark subject matter makes it an unlikely candidate for the Disney treatment that could catapult it into the mainstream anytime soon.

Maria Tatar, a Harvard professor and the author of “Secrets Beyond the Door: The Story of Bluebeard and His Wives” (Princeton University Press), said that teaching fairy tales to her students and researching the book convinced her that the tale of Bluebeard had fallen into a “cultural black hole”; she encountered few Americans who were able to recite the details of the story, despite its cultural resonance.

“I’m always astonished at how few people know this story,” she said in a phone interview, “especially considering how many films and other works it has inspired.” Ms. Tatar noted that Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” and Daphne du Maurier’s “Rebecca” owe something of their plots to the spirit of “Bluebeard.” And she devotes a section of her book to a raft of films made in the 1940s, including George Cukor’s “Gaslight” (1944), Alfred Hitchcock’s “Notorious” (1946) and Fritz Lang’s “Secret Beyond the Door ...” (1948), that do not overtly reference the tale but nevertheless turn on a wife’s fear of her largely unknown husband and his possible desire for her throat. More recently, Jane Campion featured a Bluebeard pantomime in her 1993 film “The Piano.”

Ms. Breillat’s film moves between a re-enactment of the centuries-old fairy tale and the 1950s, when a girl reads Perrault’s tale aloud to her older sister, as Ms. Breillat did in her youth.

Known as the writer-director of cerebral, sexually explicit films like “Romance” (1999), “Fat Girl” (2001) and “Anatomy of Hell” (2004), Ms. Breillat insisted that nudity and sex have no place in her favorite childhood fairy tale. In her film the only glimpse of flesh involves Bluebeard’s corpulent torso. But that doesn’t mean that she doesn’t see sex as one of the story’s primary themes.

Perrault’s tale ends with a tacked-on moral about the fleeting pleasures and damning consequences of a woman’s curiosity, but Ms. Breillat favors a Freudian interpretation: the bloody key as a symbolic nod to the loss of the heroine’s virginity.

“That key imposes a certain destiny,” Ms. Breillat said in her home on a cobblestone street in the 20th Arrondissement, sipping tea in her kitchen. “He is obliged to kill her, but he can’t.”

Ms. Breillat takes pains to humanize Bluebeard and to show what she believes is real love between him and his young wife; her Bluebeard, for example, treats his virginal 14-year-old bride with paternal affection, allowing her to sleep alone in the one room in the castle whose threshold is literally too narrow for his girth. With his feminizing corpulence he is more gentle giant than monster.

“My Bluebeard is very touching,” she said. “He’s like a father to her. But fathers can be very cruel to their daughters. I think fundamentally ‘Bluebeard’ is a metaphor about the tender and cruel relationship between men and women.”

Terrifying stories like “Bluebeard” can function as a sort of exorcism for our fears, Ms. Breillat said, allowing us the luxury of frightening ourselves in the safety of our imaginations to emerge better able cope with the real horrors of living.

"The difference is that children are fascinated by fear because they are invincible,” she said. “They know it won’t happen to them. As adults we project ourselves onto those corpses in the basement."

In 2004, two weeks before she was originally scheduled to start shooting “Bluebeard,” Ms. Breillat had a cerebral hemorrhage that paralyzed her left side. Once she had taught herself to speak and walk again, she said, she could not yet face tackling her favorite fairy tale and instead made “The Last Mistress,” a costume drama based on an 1865 novel by Jules Amédée Barbey d’Aurevilly.

“I was afraid to do ‘Bluebeard,’ ” she said, “because it is such a fundamentally black story. In all the other fairy tales the ogre is an ogre; he’s a monster. ‘Bluebeard’ is so very dark because in the end the ogre isn’t an ogre. He’s a man.”

Kristin Hohenadel

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/28/movies/28bluebeard.html?ref=movies

After the Wedding Bells Comes the Drama for the Wife of Bluebeard

Psychologically rich, unobtrusively minimalist, at once admirably straightforward and slyly comic, Catherine Breillat's Bluebeard is a lucid retelling and simultaneous explanation of Charles Perrault's nastiest, most un-Disneyfiable nursery story. This gruesome account of a wealthy serial wife-killer (the most celebrated ogre this side of Shrek) picks up where other fairy tales end. As noted by novelist Alison Lurie, "the real trouble begins after the wedding."

Though some have given "Bluebeard" relatively short shrift—child psychologist and author Bruno Bettelheim characterized it as a cautionary fable on the perils of female curiosity and "destructive aspects of sex"—the hirsute gynocidal maniac has been a rich subject for literary feminists. "Bluebeard" served as the basis for Angela Carter's most famous story, "The Bloody Chamber," and gave Margaret Atwood the title for one of her collections; it provided Maria Tatar with the basis for a book, Secrets Beyond the Door (which commented on Hollywood's many wartime versions of the story), and occasioned a major essay by Marina Warner (who suggested that the bloody corpses stashed in Bluebeard's secret room represent the "historic dangers of childbirth").

Breillat, who prizes sexual curiosity above all and claims to have loved "Bluebeard" as a child, gives the tale her own spin. The idiosyncratic artist reimagines the perverse bedtime story as one of sibling rivalry, adding a measure of religion and soupçon of class awareness to the mix. Bluebeard opens in a 17th-century convent school, "Kyrie Eleison" trilling on the soundtrack, from which, due to their tuition-paying father's sudden death, two teenaged sisters are expelled. En route home, the newly indigent girls pass Bluebeard's castle: The younger, Marie-Catherine (Lola Créton), expresses interest, while elder sister Anne (Daphné Baiwir) primly notes that "the poor have to work their hides off for the rich."

As blunt as the unconscious mind, this is a movie in which everyone always says what they're thinking. The sisters fervently wish death on the mother superior even as their own mother curses her luck that they were born ("How will I marry you off?"), boiling their clothing in black dye. The furniture has been repossessed and the family is living on grass soup when a dashing young messenger arrives with an invitation to Lord Bluebeard's party. "You'd have to be poor to love him," Anne sniffs, as if her sister didn't know; the inevitable, church-sanctified marriage ceremony ends with a cascade of gold coins poured over Marie-Catherine's head.

A terse 80 minutes, Bluebeard has the modest period quality of Roberto Rossellini's historical films. As lurid as her material is (and as provocative as she can be), Breillat is here remarkably restrained. The discrepancy in size between the expansive monster (Dominique Thomas) and his scrawny, barely pubescent child-bride teases the imagination, as does the scene when, having established that she will sleep in a broom closet until she turns 20, Marie-Catherine spies on Bluebeard's enormous comatose body. It's gross, to be sure, although the movie's most explicit image is a lengthy shot of a decapitated fowl's bloody, twitching carcass. Is it the end of Mother Goose or a premonition of the movie's designated dead duck?

Adding to the chaste perversity, Breillat has framed and interrupted Perrault's story with two small modern-day girls, the impish Catherine (Marilou Lopes-Benites) and her older sister, Marie-Anne (Lola Giovannetti), who are themselves reading "Bluebeard." The girls are not only named for Breillat and her sister, but, according to the filmmaker, are wearing their actual childhood dresses. The irrepressibly provocative Catherine teases Marie-Anne, who is made anxious by "Bluebeard," as a "scaredy-cat," while offering her own extravagant notions of human nature (married couples are "homosexual when they're in love"). The child is mother to the woman: As a pint-size theorist, little Catherine anticipates the grown Breillat.

The sister act has echoes of Breillat's Fat Girl, as rival sibs negotiate their coming-of-age, and Bluebeard's ending is similarly abrupt. Actually, the movie has two punch lines. In one narrative, Breillat flips the original tale's emphasis from the helplessness of women to their resourcefulness; in the other, she invokes the power of fantasy to disrupt your very life.

http://www.villagevoice.com/2010-03-24/film/after-the-wedding-bells-comes-the-drama-for-the-wife-of-bluebeard/

Q&A with Bluebeards Catherine Breillat

With Bluebeard, Catherine Breillat—perhaps the most willful feminist provocatrice in cinema today, whose stroke in 2004 made her even more determined to keep working—slyly subverts Charles Perrault's gruesome fairy tale about a young bride married to an aristocrat who has murdered his previous wives. Of the many adaptations of Perrault's 1697 story showing at Anthology's "Bluebeard on Film" series this week, Breillat's version is the most personal: By inserting semiautobiographical scenes of two sisters in the 1950s who are fascinated with this grisly narrative, she creates a clever framing device to explicate a 300-year-old tale, itself a story involving two sisters. As the film toggles between the 17th and 20th centuries, the director makes keen observations about sibling rivalry, sexual curiosity, notions of purity and innocence, and the power of language and imagination. In town last October for Bluebeard's New York Film Festival premiere, I met with Breillat, 61, to talk about sororal breakups, reconciliations, and Naomi Campbell.

What's your connection to Perrault's fairy tale? I like that Bluebeard isn't an ogre or a giant—he's a man. It struck me that girls read this tale at a very young age: I myself read it when I was five. It's a story that teaches these little girls to love the man who's going to kill them.

Bluebeard is a story about the dangers of female curiosity, a theme that runs through many of your films. Must it always have such dire consequences? In my film, the consequences are dire for him, not for her. In the past, we've had stories like Eve, who takes the apple of knowledge and tempts Adam to bite into it. So she's the one who's guilty—she's responsible. Here, it's he who's responsible. He's the one who holds the tiny key out to her. As a very young girl, I was drawn to the image of the [murdered] wives hanging in the room—I love this image of the eternally fresh blood that was like a mirror under them. That, to me, is a vision of the eternity of women.

In both Bluebeard and 2001's Fat Girl, about two siblings on summer vacation, you explore the ties between sisters. What is it about this relationship that fascinates you? Because I am the younger sister, and my sister was the older sister. [Laughs.] We're very close in age, separated by only 13 months, so we always loved each other, but we also hated each other passionately. My sister never wanted me to deal with the subject of sisters in my films, and I respected that up until Fat Girl. And though she didn't see the film, it made her furious with me, and we had a rupture as a result. When it came time to make Bluebeard, I figured I didn't have to pull any punches and I could kill her off, since we weren't on speaking terms anyway. [Laughs.] But she saw the film, and, oddly enough, we've reconciled.

Is the relationship between sisters inherently a sadomasochistic one? It depends on whether the parents contribute to that or not. Our parents forced us to be together constantly. I had to be my sister's best friend, and she had to be mine. There's no escape valve in a relationship like that. On top of that, because of the small difference in our age, people outside the family were constantly mistaking us. That's something that's unbearable to you as a child.

When we met in the fall of 2007, you mentioned a project that you were working on with Naomi Campbell called Bad Love, about a woman in a destructive relationship— Naomi, Naomi. Naomi's a wonderful actress, but because she doesn't speak French, we'd have to shoot the film in English. And it's impossible to find funding to shoot a film [in France] in English unless you're a very commercial director. That said, I'm a very stubborn filmmaker, and I haven't given up hope. The only problem is that I'm getting older every day.

I've read that Bad Love won't be made because notorious con man Christophe Rocancourt, the film's male lead, swindled you out of 650,000 euros. Is this true? No, it is not true. Christophe Rocancourt is totally replaceable. Doing a film in English is a major problem. [Note: Breillat published a book about the Rocancourt incident called Abuse of Weakness in November 2009.]

If Naomi agreed to take French lessons and do the film in French, would you be able to secure funding? You need a certain truth. We did some tests in English, and she was magnificent. The problem, however, is that French with an English accent just isn't very pleasant to hear. There's another complication: A crime took place in France with a similar story [to mine]—a wonderful French actress [Marie Trintignant] was murdered [in 2003] by her boyfriend. The feeling is that if I make this film, even though women are so often killed by their boyfriends, it will somehow reawaken the pain of the mother [Nadine, a writer/director], who's also famous. People suspect that I'm trying to draw on the box-office appeal of that story, even though it's a subject I've wanted to make a film about for more than 10 years. I absolutely want to do the film.

Bluebeard screens March 3 as part of Anthology's "Bluebeard on Film" and opens theatrically March 26 at the IFC Center

Tuesday, March 2, 2010 at 4 a.m.

By Melissa Anderson

http://www.villagevoice.com/2010-03-02/film/q-a-with-bluebeard-s-catherine-breillat/